Wired.com is running a good piece on the price of the operating systems. It covers a bit of history and shows how things are now and how it all came a full circle – from free operating systems of the past, all through highly profitable years of Microsoft and Apple, and back to free operating systems of today’s mobile world.

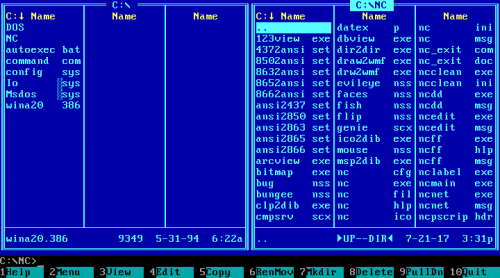

In a way, operating systems are returning to their roots as a kind of loss leader. Before the personal computer revolution of the late 1970s, operating systems were just one piece in a vertically integrated stack of technology, a stack that also included hardware and support services. Operating systems like Unix and VMS were used to sell minicomputers and workstations, and companies made their profits on hardware and support contracts. OSes such as BSD UNIX were completely free, and programmers would pass them around at will. Under the same philosophy, Apple gave away new versions of its Macintosh operating system until the crisis years of the late 1990s, when hardware sales slowed dramatically.

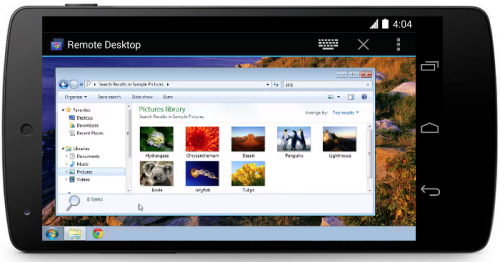

In the rapidly developing smartphone and tablet markets, tightly-coupled stacks are once again dominant, so OS makers can subsidize their operating systems with profit from the products integrated into them. Google, for example, subsidizes its mobile OS by selling online ads, and, in theory at least, by selling Motorola-branded hardware. Apple’s iPhone profits come from hardware and service sales, not the OS.

The article also shows how problematic is this new situation for Microsoft.

Microsoft’s OS sales once generated 47 percent of its revenue, but they contributed just 25 percentlast year on decelerating Windows licensing (and even that figure is inflated by ad revenue from Windows Live). In response, Microsoft is restructuring as a “devices and services” business — meaning a company that sells hardware like the Xbox and web services like Azure. In other words, it’s becoming more like Apple. Apple isn’t really a software company. It makes software and services that run on its own hardware devices.

However …

Yes, even Microsoft is moving towards the vertical stack. It recently acquired phone maker Nokia and sells its own tablets. But this game of cross-subsidizing the operating system will be tougher for Microsoft, since the company is no Apple when it comes to hardware — and no Google when it comes to online services. The company rose to prominence in the horizontal PC era, when Microsoft could play one hardware vendor against another, dictate prices, and keep a computer’s hefty OS markup hidden from consumers. Those were the days.

And more specifically:

So to the average consumer, the 21st Century sea change in OS pricing might not be particularly apparent. But to Microsoft shareholders, it will look very real and very scary. The company must make up that 25 percent somewhere else.

It’ll be interesting to see how it plays out.