If the World War III will ever start, it won’t be for oil or food. It will be the whole world jumping on China, in an attempt to destroy every single computer running Microsoft Internet Explorer 6.

Tag: China

Chinese New Year

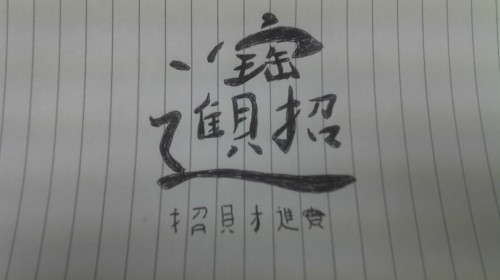

I’ve mentioned a few times on this blog that I’m a big fan of Chinese culture. Today, at the office, we had Chinese New Year celebrations will plenty of home-made food (cooked by our Chinese colleagues) and red decorations all around. That inspired me to read some more about China on Wikipedia and even try my hand at calligraphy.

The above image depicts my third attempt, which was good enough to be readable and was actually recognized by at least one Chinese person as “this is actually pretty good“. Let’s all call that my best wishes for all of you this year.

P.S.: If you wander what that one means, I used this image as the source of inspiration. Wikipedia says it means “When wealth is acquired, precious objects follow”. Having no idea myself, I’m inclined to trust that.

Death by a thousand clicks

If you don’t know or remember the expression “death by a thousand cuts”, it refers to an ancient Chinese torture.

Slow slicing [..], also translated as the slow process, the lingering death, or death by a thousand cuts [..], was a form of execution used in China from roughly AD 900 until its abolition in 1905. In this form of execution, the condemned person was killed by using a knife to methodically remove portions of the body over an extended period of time. The term língchí derives from a classical description of ascending a mountain slowly. Lingchi was reserved for crimes viewed as especially severe, such as treason and killing one’s parents. The process involved tying the person to be executed to a wooden frame, usually in a public place. The flesh was then cut from the body in multiple slices in a process that was not specified in detail in Chinese law and therefore most likely varied. In later times, opium was sometimes administered either as an act of mercy or as a way of preventing fainting. The punishment worked on three levels: as a form of public humiliation, as a slow and lingering death, and as a punishment after death.

Then, of course, there is a modern day office variant – “death by a thousand papercuts”, which I won’t go into any detail – you can get the idea.

Well, today I discovered yet another, even more modern variation of that – death by a thousand mouse clicks. And even if you’ve heard that before in regards to a bad user interface, there is another meaning to it. Yesterday I paper cut my right index finger. While it’s not that bad on its own, when combined with a mouse button it is indeed a new form of torture.

Do you have any idea how many times you click, double-click and wheel-scroll every day? A lot! I tried to count but I don’t know a number that large. Except gadzillion, to which I don’t know how to count. Anyway, even if you don’t use your mouse so much, you still need to type, don’t you? And typing with the cut on the index finger is more annoying than with any other finger. All because of those little nobs they put on keys F and J so that you could find the home row. Good thing I’m not bleeding at least…

Waves brought by typhoon Nesat

Big Picture covers the typhoon Nesat that caused havoc in several Asian countries – India, Pakistan, China, Thailand, Philippines. While most of the pictures there attempt to show the scale of the destruction and suffering, I was mesmerized by this one, which displays the powers of nature.

The End of Cheap Labor in China

Slashdot links to this article, that goes inline with this recent forecast.

In what is supposed to be a land of unlimited cheap labor — a nation of 1.3 billion people, whose extraordinary 20-year economic rise has been built first and foremost on the backs of low-priced workers — the game has changed. In the past decade, according to Helen Qiao, chief economist for Goldman Sachs in Hong Kong, real wages for manufacturing workers in China have grown nearly 12% per year. That’s the result of an economy that’s been growing by double digits annually for two decades, fueled domestically by a frenzied infrastructure and housing build-out — one that, for now anyway, continues apace — combined with what was for a time an almost unquenchable thirst for Chinese exports in the developed world. Add to that the fact that in the five largest manufacturing provinces, the Chinese government — worried about an ever widening gap between rich and poor — has raised the minimum wage 14% to 21% in the past year. To Harley Seyedin, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in South China, the conclusion is inescapable: “The era of cheap labor in China is over.”