If you are trying to learn Git, but the Git Book looks large and intimidating to you (which it isn’t), have a look at Git Magic. It’s smaller and simpler, and seems like a good start for those of you just getting your feet wet in the git world.

Tag: version control

On Empathy & Pull Requests

I’ve trained more people on the subject of pull requests than I care to remember. But I’ve never came close to explaining the best practices as well as this Slack Engineering blog post does:

Basically, your reviewer is totally missing context, and it is your pull request’s job to give them that context. You have a few options:

- Give it a good title, so people know what they’re getting it into before they start.

- Use the description to tell your reviewer how you ended up with this solution. What did you try that didn’t work? Why is this the right solution?

- Be sure to link to any secondary material that can add more context — a link to the bug tracker or a Slack archive link can really help when describing the issue.

- Ask for specific feedback — if you are worried that the call to the `fooBarFrobber` could be avoided, let them know that so they can focus their effort.

- Finally, you should explain what’s going on for your reviewer. What did you fix? Did you have any trouble fixing the bug? What are some other ways you could’ve fixed this, and why did you decide to fix it this way?

Not every pull request needs every single one of those things, but the more information you give your reviewer, the better they will be able to review your code for you. Plus, if someone ever finds a problem in the future and tracks it down to this pull request, they might understand what you were trying to do when they make a follow-up fix.

Give your reviewer all the context they need to get up to speed with your bug so they can be an informed, useful code reviewer. It’s all about getting your reviewer onto the same page as yourself.

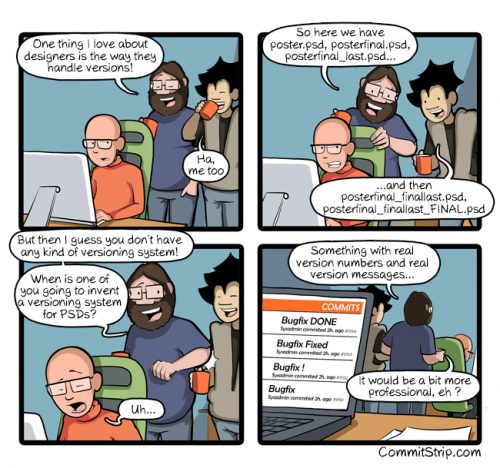

On Semantic Versioning

First of all, you should know that versioning is important. Even the worst versioning practices provide more value than no versioning at all. At work, we are big fans of the Semantic Versioning, and we use it for all our projects, plugins, and libraries. And I think, you should do too.

In general, Semantic Versioning works great for us. But there were a few bumps recently, with more and more libraries dropping support for PHP 5.6 and requiring PHP 7. I can’t blame them – after all PHP 5.6 has reached its end of life quite a while ago.

It’s not what the maintainers do, but how they do it that I have an issue with. I’ve been thinking about writing a blog post on the subject for a few month now. Never got to it. And yesterday I came across this blog post by Paul Jones, which is so much better than whatever I was about to say. Paul explains the problem in detail and suggests the “System” addendum to Semantic Versioning:

I opine that requiring a change in the public environment into which a package is installed is just as major an incompatibility as introducing a breaking change to the public API of the package. To cover that case, I offer the following as a draft addendum to the SemVer spec:

- If the package consumer has to change a publicly-available system resource to upgrade a package, then the package upgrade is not backwards-compatible with the existing system, and the package SHOULD receive a major version bump.

Using “SHOULD” makes this rule somewhat less strict than the MUST of a major version bump when changing the package API.

Coming back to PHP 5.6 vs PHP 7, that would suggest that maintainers who drop support for PHP 5.6 SHOULD bump up the MAJOR release of the library. And I wholeheartedly agree with that!

P.S.: For those of you who don’t or can’t use Semantic Versioning for whatever reason, checkout Paul’s blog post on Semantic Versioning vs. Romantic Versioning.

pre-commit – a framework for managingmulti-language git pre-commit hooks

From the pre-commit homepage:

Git hook scripts are useful for identifying simple issues before submission to code review. We run our hooks on every commit to automatically point out issues in code such as missing semicolons, trailing whitespace, and debug statements. By pointing these issues out before code review, this allows a code reviewer to focus on the architecture of a change while not wasting time with trivial style nitpicks.

As we created more libraries and projects we recognized that sharing our pre-commit hooks across projects is painful. We copied and pasted unwieldy bash scripts from project to project and had to manually change the hooks to work for different project structures.

[…]

We built pre-commit to solve our hook issues. It is a multi-language package manager for pre-commit hooks. You specify a list of hooks you want and pre-commit manages the installation and execution of any hook written in any language before every commit. pre-commit is specifically designed to not require root access.

Have a look at the list of all supported hooks. There’s plenty!

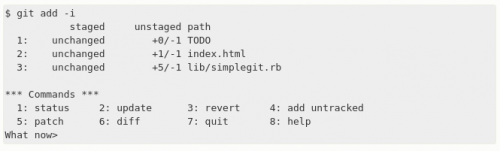

git add –patch and –interactive

I knew about git interactive staging for a while now, but I’ve never really used it. Most days I work on a single feature or bug fix at a time and can commit sequentially, one change after another. For an occasional mess, I found git interactive staging user interface too be too cumbersome.

The last couple of days at work were quite chaotic, with me jumping from one thing to another, and I decided to master that feature once and for all. Looking for a better tutorial, I came across this blog post, which covers the interactive staging, but also provides a much simpler approach – “git add –patch“.

It’ll take some practice to get it into my finger memory, but I think I’m settled now.