Way too often I hear rants from random people (unfortunately, many of them are also from the IT industry, with the deep understanding of the underlying issues) complaining about why company X or product Y doesn’t implement this or that feature. As someone who has been involved a dozens, if not hundreds, of projects, I pretty much always can think of a number of reasons why even seemingly the simplest of features aren’t implemented for years. These can vary from business side of things – insufficient budgets, strategic goals, and the like – to technical, such as architectural limitations, insufficient expertise, insufficient resources, etc.

One of the recent frequent rant that keeps coming up is “Why don’t they just enable HTTPS?”. Again, as someone being involved in HTTPS setup for several different environments I can think of a number of reasons why. SSL certificates used to cost money and were quite cumbersome to install until very recently. Thanks to Let’s Encrypt effort, SSL certificates are now free and quite easy to issue and renew. But that’s only part of the problem. Enabling HTTPS requires infrastructural changes, and the more complex your infrastructure, the more changes are needed. Just think of a few points here – web server configuration (especially when you have multiple web servers, with varied software (Apache, Nginx, IIS) and varied versions of that software), load balancers, web application firewalls, reverse proxies, caching servers, and so on.

Apart from the infrastructural changes, HTTPS often needs changes on the application level. Caching, cookies, headers, making sure that all your resources are HTTPS-only, redirects, and the like.

All of the above issues are multiplied by a gadzillion, when your project is publicly available, used by tonnes of people, and provides embeddable content or APIs to third-party (hello, backward compatibility).

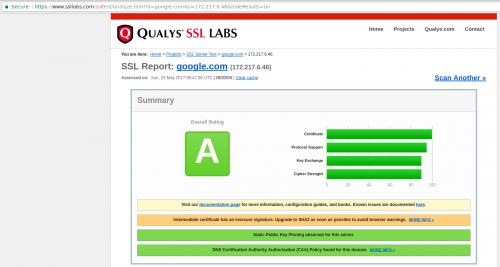

This is not to mention that HTTPS itself is a complex subject, not well understood by even the most experienced system administrators and developers. There are different protocols and versions (SSL vs. TLS), cipher suites, handshakes, and protocol details. Just have a look at the variety of checks and the report length done by Qualys’ SSL Labs Server Test. Even giants like Google, who employ thousands of smart people, can’t get it all right.

But for some reason, people either don’t know or prefer to ignore all this complexities, and whine and cry anyway.

Recently, Stack Overflow – a well known collection of sites on a variety of technical subjects, has completed the migration to HTTPS everywhere. These are also people with a lot of knowledge and expertise and with access to all the information. Just have a look at their long way, which took not months, but years: HTTPS on Stack Overflow: The End of a Long Road.

Today, we deployed HTTPS by default on Stack Overflow. All traffic is now redirected to

https://and Google links will change over the next few weeks. The activation of this is quite literally flipping a switch (feature flag), but getting to that point has taken years of work. As of now, HTTPS is the default on all Q&A websites.We’ve been rolling it out across the Stack Exchange network for the past 2 months. Stack Overflow is the last site, and by far the largest. This is a huge milestone for us, but by no means the end. There’s still more work to do, which we’ll get to. But the end is finally in sight, hooray!

So next time you are about to start crying about somebody not having feature X or Y, just give it a minute first. Try to imagine what goes on on the other side. You aren’t the only one with low budgets, pressing deadlines, insufficient knowledge, bad colleagues and horrible bosses…