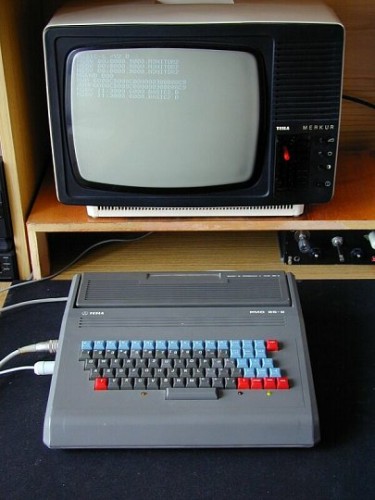

Once in a while people ask me what was the first computer I could get my hands on. Mistakenly, I’ve often answered that it was Commodore 64. But today I did some digging and realized that it wasn’t true. I did use Commodore 64 too, but that was mostly for playing games – my uncle was a head of a nearby Fire Station and he had one of these in the office, but that wasn’t the first computer I used, and it wasn’t the one I learned to program on. That honor goes to Tesla PMD 85-1. Here is a picture to give you an idea (thanks to root.cz):

We had a computer lab in school, with 11 of these things. 10 were used by the students and 1 was for the master station for the teacher. Some of the highlights that I still remember: black and green monitor, cassette tape drive for loading and saving programs (sorry, no hard drives or floppies, or network really, except for printing on a slow and very load dot-matrix printer), a very uncomfortable yet colorful keyboard. The keyboard is worth a separate mention. As seen above, it had blue, red, and grey keys. It didn’t have an Enter or Escape keys. But it had two EOL (end of line) keys right next to each other – I don’t remember why though. And STOP and RST (reset) buttons. And it was almost QWERTY. Here is a close-up image from Wikipedia:

For some reason, I remember the keyboard slightly different. Those blue K-keys were to the left of the main area, organized into two vertical columns. But I was unable to find an image of such model, so it must be my memory failing.

When I was back in 5th grade (that must have been … hmm … somewhere around the year 1990), a new Informatics (that’s how Computer Science was called back then) teacher at school opened up an after hours Computer Club, which allowed all students, and not just the high graders access to the machines. I don’t remember the name of the guy, or how I got involved with it, but I do remember that I got hooked on it pretty much immediately.

A few times a week, we’d stay for an hour or two after classes and learn Basic programming language. He’d explain to us some basic concepts such loops, conditions, and variables, and then would let us work on our code. For the rest of the days, I remember, I was walking around with the paper notepad, in which I’d write source code by hand, debug it, test it, and improve it, so that I could spend less time doing so in the lab. Machine time was limited (an hour or two per session, with some of it taken for loading the program from tape, typing in changes, and saving back to tape), so you’d optimize for using it to actually run the program, verify the result, and, maybe, try one or two more ideas.

If I remember correctly, I worked on these machines for two or three years. Then, my other uncle, who was the first real IT guy I knew, got me an IBM XT machine. It wasn’t an original IBM, but a mix of Soviet countries manufacturers. But that was great! That was the closest thing to the modern PC – CGA graphics with 4 colors, 640 KB of RAM, 10 MB hard disk, and a floppy drive! I thought nothing better was possible until I saw a VGA monitor with 16 colors. I think then I realized that I’ll never catch up to the technology developing so fast.

And one last bit of memory. Even though I wrote quite a bit of Basic code while learning English in a specialized school, it wasn’t until I came to Cyprus and started learning Pascal programming language in Intercollege, that I realized that all those words I’m typing into the computer to make it do things are ACTUAL ENGLISH WORDS! Now that was both embarrassing and empowering at the same time…

Oh, good old days.

P.S.: Yes, I’ve played on Atari too at my friends’, but I never owned one of those.