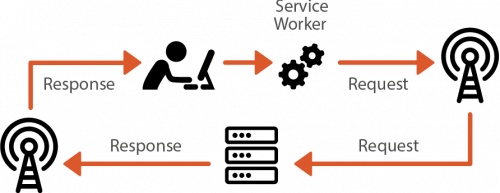

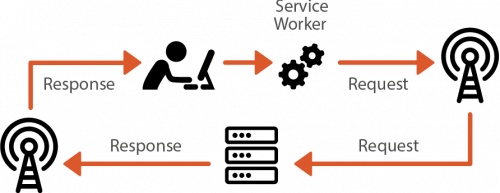

A List Apart runs an excellent article “Going Offline“. In it, among other things, there’s one of the simplest explanations of the Service Workers technology that I’ve seen so far:

A service worker is like a cookie. Cookies are downloaded from a web server and installed in a browser. You can go to your browser’s preferences and see all the cookies that have been installed by sites you’ve visited. Cookies are very small and very simple little text files. A website can set a cookie, read a cookie, and update a cookie. A service worker script is much more powerful. It contains a set of instructions that the browser will consult before making any requests to the site that originally installed the service worker.

A service worker is like a virus. When you visit a website, a service worker is surreptitiously installed in the background. Afterwards, whenever you make a request to that website, your request will be intercepted by the service worker first. Your computer or phone becomes the home for service workers lurking in wait, ready to perform man-in-the-middle attacks. Don’t panic. A service worker can only handle requests for the site that originally installed that service worker. When you write a service worker, you can only use it to perform man-in-the-middle attacks on your own website.

A service worker is like a toolbox. By itself, a service worker can’t do much. But it allows you to access some very powerful browser features, like the Fetch API, the Cache API, and even notifications. API stands for Application Programming Interface, which sounds very fancy but really just means a tool that you can program however you want. You can write a set of instructions in your service worker to take advantage of these tools. Most of your instructions will be written as “when this happens, reach for this tool.” If, for instance, the network connection fails, you can instruct the service worker to retrieve a backup file using the Cache API.