There’s plenty of talk about security when it comes to giant technical companies, like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple. But that’s all usually from the perspective of the software security and end-user privacy. Here’s a different perspective on the subject – “The Millions Silicon Valley Spends on Security for Execs“.

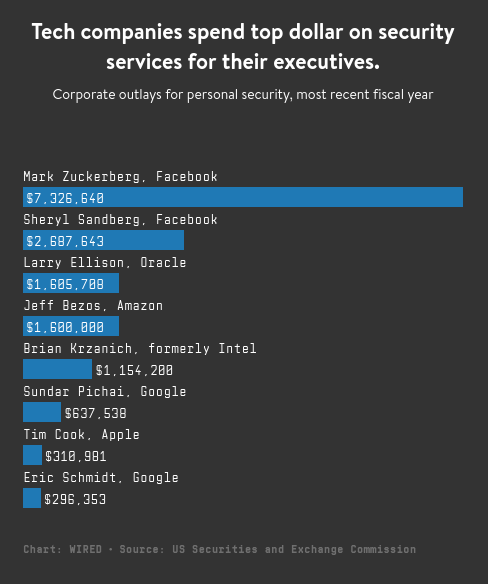

Apple’s most recent proxy statement, filed earlier this month, shows the company spent $310,000 on personal security for CEO Tim Cook. But that’s a fraction of other tech giants’ expenditures.

Amazon and Oracle spent about $1.6 million each in their most recent fiscal years to protect Jeff Bezos and Larry Ellison, respectively, according to documents filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. And Google’s parent company, Alphabet, laid out more than $600,000 protecting CEO Sundar Pichai and almost $300,000 on security for former executive chair Eric Schmidt. In 2017, Intel spent $1.2 million to protect former CEO Brian Krzanich. Apple, Google, Intel, and Oracle declined to comment; Amazon did not respond to a request for comment.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was the costliest executive to protect; Facebook spent $7.3 million on his security in 2017, and last summer the company told investors that it anticipated spending $10 million annually.

Well, that’s pretty impressive in terms of money! But do they need it really? They do, at least, to some degree:

While Silicon Valley firms haven’t disclosed many threats to the safety of their executives or offices, they have good reason to take precautions. In December, Facebook evacuated its headquarters after the company received a bomb threat. Last year an unhappy YouTube user entered the company’s San Bruno, California, headquarters and shot three employees before killing herself. And in 1992 the president of Adobe, Charles Geschke, was kidnapped at gunpoint and rescued by the FBI.

Do you still dream of being an executive in a large company?